Listen

to Katherine Kennard

reading this story

CULTURAL LANDSCAPES

CAM Gulbenkian

As the morning sun casts a glow across Lisbon, our eyes take in the unfathomable walls of lush foliage encircling the Gulbenkian Garden. We are standing at the northern entrance, between the São Sebastião and Praça de Espanha neighbourhoods, at the heart of Portugal’s bustling capital. Though removed from the heavily touristic districts, it remains surrounded by a patchwork of residential blocks, shops and cultural landmarks. Once a key gateway into the city during the 18th century, this area now forms a vibrant crossroads of daily life.

We walk towards it with determination, passing quiet corners where locals linger, the air carrying faint echoes of wildlife. For many, this oasis offers a respite – a place to retreat with a book and sink into the tranquillity of the garden. For others, it serves as a green artery, guiding commuters through its serene pathways, bridging the city’s pulse with its moments of stillness.

Crossing the threshold from the street to the garden feels almost like an out-of-body experience. By stepping foot into this ethereal kingdom of myriad fauna and flora, we can no longer hear the hustle and bustle of traffic, the customary noise that envelops our day-to-day lives without us even realising it. A loud silence reigns.

The stone-paved labyrinthine trails guide us through a dense, heterogeneous forest, intersected by small clearings and nooks, with an expansive lake at its midpoint, deepening the relationship between man and nature. It is no surprise to find mallard ducks along the way, sitting comfortably among humans; they are already used to a shared dwelling alongside sparrows, moorhens, starlings, flycatchers and many other species that found their home here decades ago, most likely even before the gardens were established in the 1960s.

“Since Japanese and Portuguese cultures have so much in common and have good chemistry, we decided to apply the engawa in this project. It is another way to experience the garden under its shadow and gentle breeze.”

KENGO KUMA

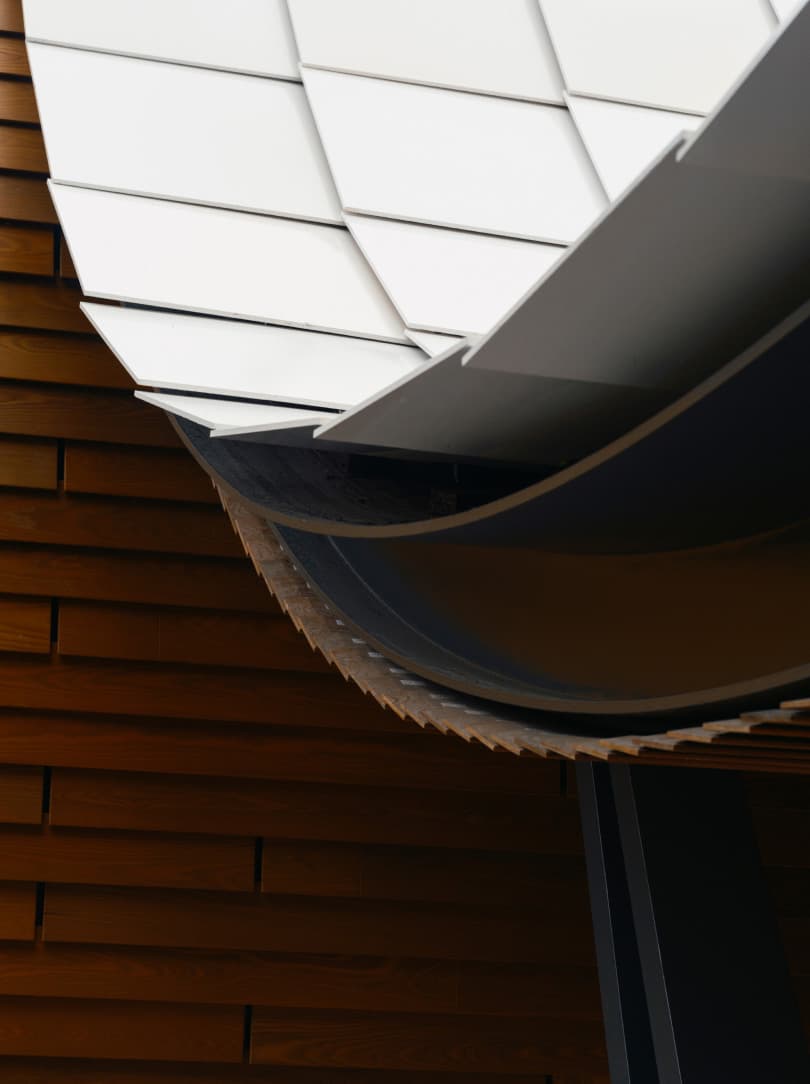

A few metres ahead, the winding footpath leads to yet another clearing, a new area of the garden that opens up to the redesigned Centro de Arte Moderna Gulbenkian (CAM). The modern art centre emerges as a contemporary deity, seamlessly interwoven with nature. Before us stands an all-embracing canopy, 107 metres long and made with exactly 3,274 Portuguese ceramic tiles, which materialise as an ‘engawa’, a sheltered walkway typically found in Japanese houses.

Behind this redesign is Japanese architect Kengo Kuma, who is one of the most prestigious architects working today, together with Porto-based studio OODA. “Since Japanese and Portuguese cultures have so much in common and have good chemistry,” Kengo explains, “we decided to apply the engawa in this project. It is another way to experience the garden under its shadow and gentle breeze.” Widely known for his ethos of ‘soft and humane architecture’, what he describes rings true.

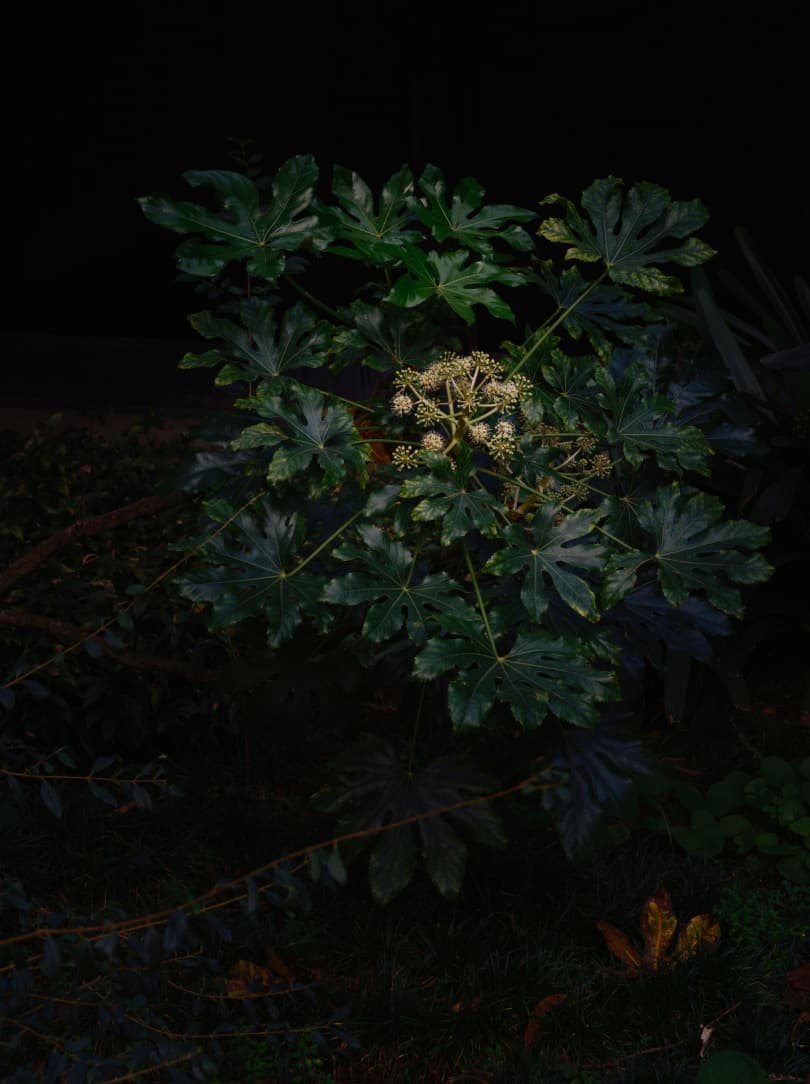

The landscape architect Vladimir Djurovic, with whom Kengo has worked extensively on other projects, came onboard to expand and enhance the distinctive landscape designed by Portuguese landscape architects Gonçalo Ribeiro Telles and António Viana Barreto in the 1960s. Vladimir’s additions stem from the original architects’ language to create what he calls an ‘urban forest’ with native flora only. A year of research brought him to select species including Polypodium vulgare, Euphorbia characias and Polygonatum odoratum, which translate into evergreen, resilient, fragrantly sweet plants, as well as cork oaks, holm oaks and Portuguese oaks. All they need now is time to become self-sufficient and ever more glorious.

Meandering along these paths brings a sense of calm, as if our minds are now able to take in everything around us in a more honest way. Our lungs feel full; our hearts whole. Earthy hues linger – dark greens, browns, creamy tinges and deep, rich wood tones. Golden leaves cover the ground. Every element seems to blend together unhurriedly, as if they have been here forever, way before us and well after us. Directly in front of the engawa, we discover a circular pond surrounded by turquoise metal chairs, colourful dots amid the seasonal shades. A feeling of warmth runs through us at the mere contemplation of people sitting, enjoying the fresh air, reading. Seeing the surrounding community coming together in such an inspiring place, inhabiting the space, brings Kengo’s vision to life in an even more profound way.

From the graceful, low-slung engawa of white tiles reflecting the ever-changing Portuguese skies to the fluid dialogue between the interior and exterior spaces, CAM also embodies a paradigm shift in the way art is encountered and perceived. The magnitude of the engawa leaves us speechless, immediately drawing us to its curvilinear traits — a refuge within the verdant expanse of the gardens. It embodies the concept of ‘ma’ (間), the Japanese notion of the ‘in-between’, where transitions become opportunities for reflection and connection. Beneath the canopy, visitors are sheltered, not confined, free to wander, explore and pause. At the engawa’s farthest edge, towering glass doors invite us into the lobby. Inside, natural light pours through transparent walls, dissolving the boundary between inside and out.

CAM was the brainchild of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation’s founding and lifetime president, José de Azeredo Perdigão, a role he held from 1956 until his demise in 1993. José was an essential player in keeping the Foundation thriving, as well as being the personal lawyer of Calouste Sarkis Gulbenkian, an Armenian philanthropist and art collector who moved to Lisbon in the 1940s and made it his home until his death. In addition to advocating quality of life through art, charity, science and education, the Foundation also came to fulfil a wish that all the art pieces Gulbenkian collected for more than 40 years would be brought together under the same roof.

CAM was envisioned in the 1970s but only opened its doors in 1983 in its original form, designed by British architect Leslie Martin, nestled in the Gulbenkian complex – which includes the Foundation’s headquarters, the museum and art library, an open-air auditorium, and 7.5 hectares of lush gardens. The underlying purpose, which still holds true today, was to house a collection of Portuguese modern and contemporary art from the 20th and 21st centuries. An avant-garde multidisciplinary programme created by Madalena de Azeredo Perdigão was launched in 1984, taking a pioneering stance that introduced critical innovations within the art world back then and continues to do so today. Her legacy lives on through CAM’s inspiring, boundary-pushing agenda.

“Art should inspire. It should shift your perspective, whether through the simplicity of a soundscape or the complexity of a contemporary installation. If we can make someone pause and see the world differently, even for a moment, we have succeeded.”

BENJAMIN WEIL

Emerging from a nearby corridor and sporting a seemingly relaxed demeanour, hands in the pockets of his corduroy trousers, with a jaunty aubergine-coloured cardigan over a white shirt, is CAM’s director, Benjamin Weil.

He greets us with a soft smile. We are advised he is feeling a bit under the weather, but that does not prevent Benjamin from enthusiastically saying hello to every employee and security guard who crosses his path. We follow him willingly into the very core of CAM towards Portuguese artist Leonor Antunes’s immersive exhibition, ‘Leonor Antunes. the constant inequality of leonor’s days*’, which has transformed the Nave and Mezzanine galleries into a sensory journey where suspended sculptures and textured floors echo the organic patterns of a forest. “Antunes’s works,” Benjamin remarks, “remind us that art is not just something to be observed; it’s something to move through, to feel with your whole being.” He explains that the interiors of this gallery have not undergone any significant transformation, a mere ‘refurbishing’ of sorts. It is an astounding space, with high ceilings, criss-crossing metal beams and pillars, tall windows and skylights.

Moving along to the contiguous Engawa Space, the unremitting dialogue with the outside world becomes clear as we spot on the ceiling the same wooden slats that cover the underside of the canopy. Here, the exhibition ‘The Occidental Calligrapher’ juxtaposes works by Portuguese-Brazilian painter and photographer Fernando Lemos with Japanese prints from the Gulbenkian Museum collections, an exploration of shared histories and artistic influences. “Art should inspire,” Benjamin reflects. “It should shift your perspective, whether through the simplicity of a soundscape or the complexity of a contemporary installation. If we can make someone pause and see the world differently, even for a moment, we have succeeded.”

“The original design by Leslie Martin never anticipated a southern entrance. What was once a blind façade now faces a lush, inviting garden. Kengo’s brilliance was to embrace this shift, making the building nearly disappear into its surroundings, allowing nature to take centre stage.”

BENJAMIN WEIL

The impetus for CAM’s reinvention stems from a pivotal acquisition by the Gulbenkian Foundation in 2005: a sprawling 8,300-square-metre plot of land south of the museum, dramatically altering the landscape and access points. “The original design by Leslie Martin never anticipated a southern entrance,” Benjamin recounts. “What was once a blind façade now faces a lush, inviting garden. Kengo’s brilliance was to embrace this shift, making the building nearly disappear into its surroundings, allowing nature to take centre stage.” The redesign thus reorients CAM’s main entrance to the south, connecting it directly to the city, and making it a more integral part of Lisbon’s cultural landscape. This change also mirrors a broader effort to democratise art, like a literal “walk in the park: unpretentious, inviting and open to all,” Benjamin adds.

We are now heading towards the lift that will take us to the new underground level, known as C1, also created by Kengo Kuma. This is where we find the Collection Gallery, a space devoted to showing CAM’s almost 12,000 works divided into segments of selected pieces by different curators to create ongoing exhibitions.

As we step into the gallery, our eyes first meet a long, velvety curtain, part of architect Diogo Passarinho’s exhibition design project. It evokes a kind of “domestic aura”, as Benjamin puts it, promptly captivating our attention with the high ceiling, with lines of soft fabric undulating across it. “It works beautifully,” he adds. “You don't feel the room is empty or too full. It helps you navigate things, and the ‘walk in the park’ metaphor keeps resonating here.” And because it is nearly impossible to display thousands of pieces at the same time, the collection will also feature prominently in two additional spaces on the same floor: the Open Storage and the Drawing Room. Both aim to present a rotating selection of works in versatile viewing rooms – directed at professionals for research, while offering visitors a chance to engage with the artworks and gain insight into the behind-the-scenes activities that underpin the institution’s work. “We want to demystify what happens behind the scenes. This transparency fosters a sense of ownership, emphasising that art belongs to everyone,” Benjamin says.

“It's really interesting to think you can experience art with your ears and not just your eyes. It demands your physical presence in this space.”

BENJAMIN WEIL

As we chat and get acquainted with CAM’s sizeable interior, we also get to know Benjamin Weil a bit more, and realise his journey is as layered as CAM itself. Born in Paris, he grew up with a restless curiosity that led him to the United States, where he spent more than two decades working in contemporary art. His résumé is a testament to his innovative spirit, spanning roles from curator of media arts at SFMOMA in San Francisco to artistic director at Centro Botín in Santander. Yet, it was the opportunity to steer CAM through its new chapter that drew him to Lisbon. “When I was approached for this role,” he tells us, “I saw an extraordinary chance not just to lead an art centre but to redefine what it means to experience art today.”

We go up to the ground floor again and are directed to the H BOX, a spaceship-looking screening room designed by French-Portuguese artist and architect Didier Fiúza Faustino. It has been travelling to museums, biennials and festivals round the world, and now stands in CAM’s expansive lobby, with a selection of 12 videos that can be selected and watched by visitors for free. Next to it, the corridor where we first spotted Benjamin is the same one we enter now, just a few steps from the Project Space, the Studio and the Sound Room. Here, Benjamin speaks enthusiastically about the installations being shown, which belong to the Japanese programme at CAM, rightfully dubbed ‘Engawa – A Season of Contemporary Art from Japan’. “The sound piece for which we commissioned a young Japanese artist, Yasuhiro Morinaga, is based on his experience living in the Amazonian forest. It's really interesting to think you can experience art with your ears and not just your eyes. It demands your physical presence in this space.”

Inside CAM, Benjamin’s vision comes alive, challenging traditional notions of art consumption. At the heart of his leadership is also a deep respect for artists. While acknowledging that they are his greatest inspiration, Benjamin contends that they have an extraordinary ability to reflect the world in ways that challenge and transform us: “Without them, none of us in this field would have a purpose.” His connection to CAM extends beyond his professional role. He finds solace in walking through the museum and gardens, observing how visitors interact with the space, like watching a story unfold, each person bringing their own narrative and way of engaging with what they see. For Benjamin, quiet moments like these are essential. “Breakfast is my favourite daily ritual,” he shares with a smile. “It's a time to centre myself, think and prepare for the day ahead.”

As we say our goodbyes, we notice that the light reflected on the canopy is noticeably different to how it was in the morning. A play of shadows projected by the surrounding trees reveals the day is approaching its final hours of sunlight. It is a reminder of the profound impact that thoughtful design can have on our shared human experience.