Play Movie

Listen

to Katherine Kennard

reading this story

Handprinted paper made in Kyoto

Ko Kado

Renowned for its rich history, the textile district of Nishijin can be found in the northwestern part of Kyoto. Home to the production of the luxurious Nishijin brocade, the area’s narrow streets are lined with wooden ‘machiya’ townhouses, while stories of craftmanship remain ever-present. Set against this backdrop of tradition, heritage and craft, the studio and shop of ‘karakami’ (decorative paper) artisan Ko Kado can be found inside a former barbershop on Kuramaguchi-dori.

Positioned alongside a heritage-listed bathhouse-turned-café, the two-storey building has stood for almost a century. Beyond the understated timber and tile façade, the ground-floor space retains traces of its barbershop past. It now functions as a retail space, presenting products, collaborations and occasionally hosting craft exhibitions. Paper is all around: adorning the walls, encasing furniture, covering panels and featuring in the selection of stationery, publications and other printed matter on display.

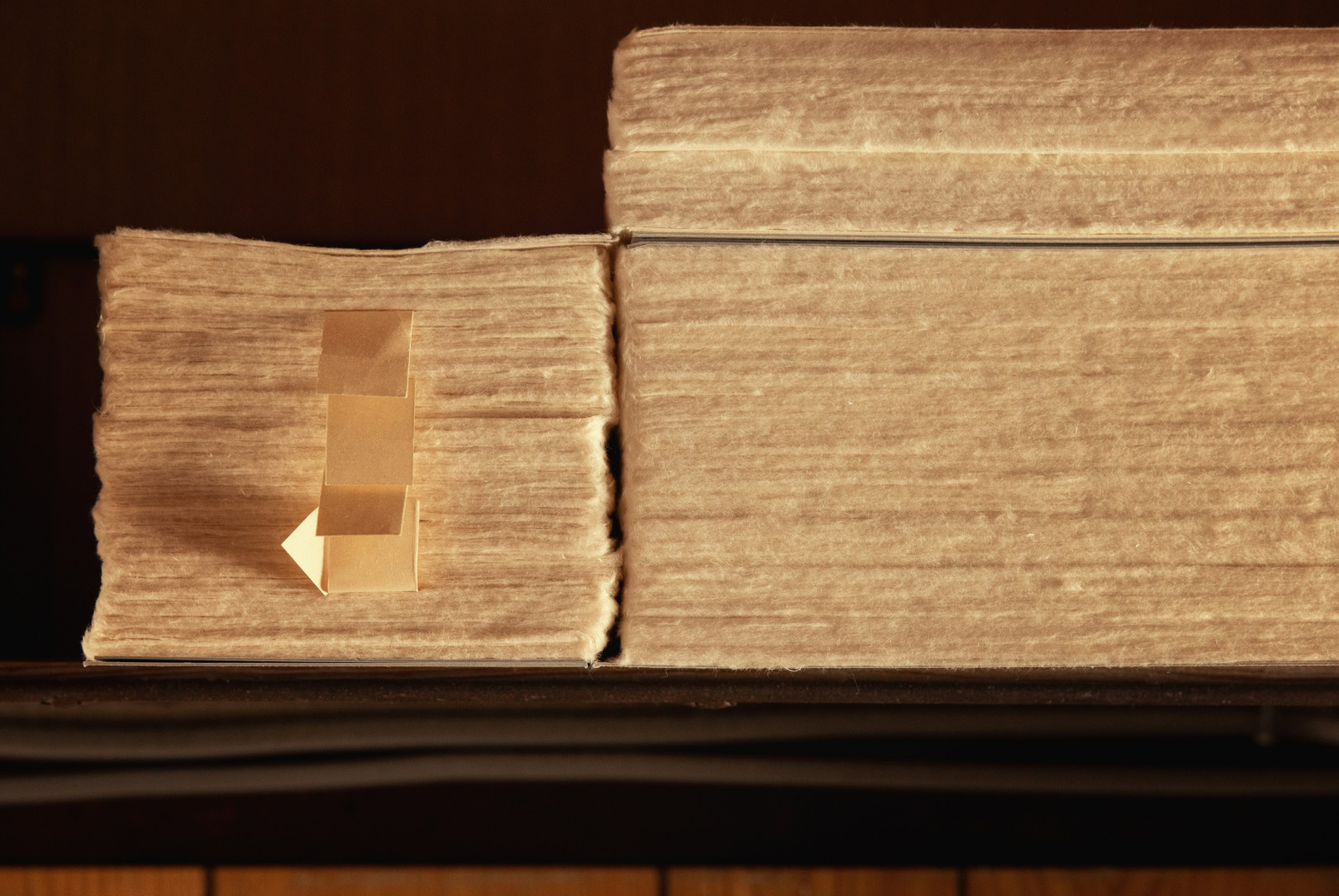

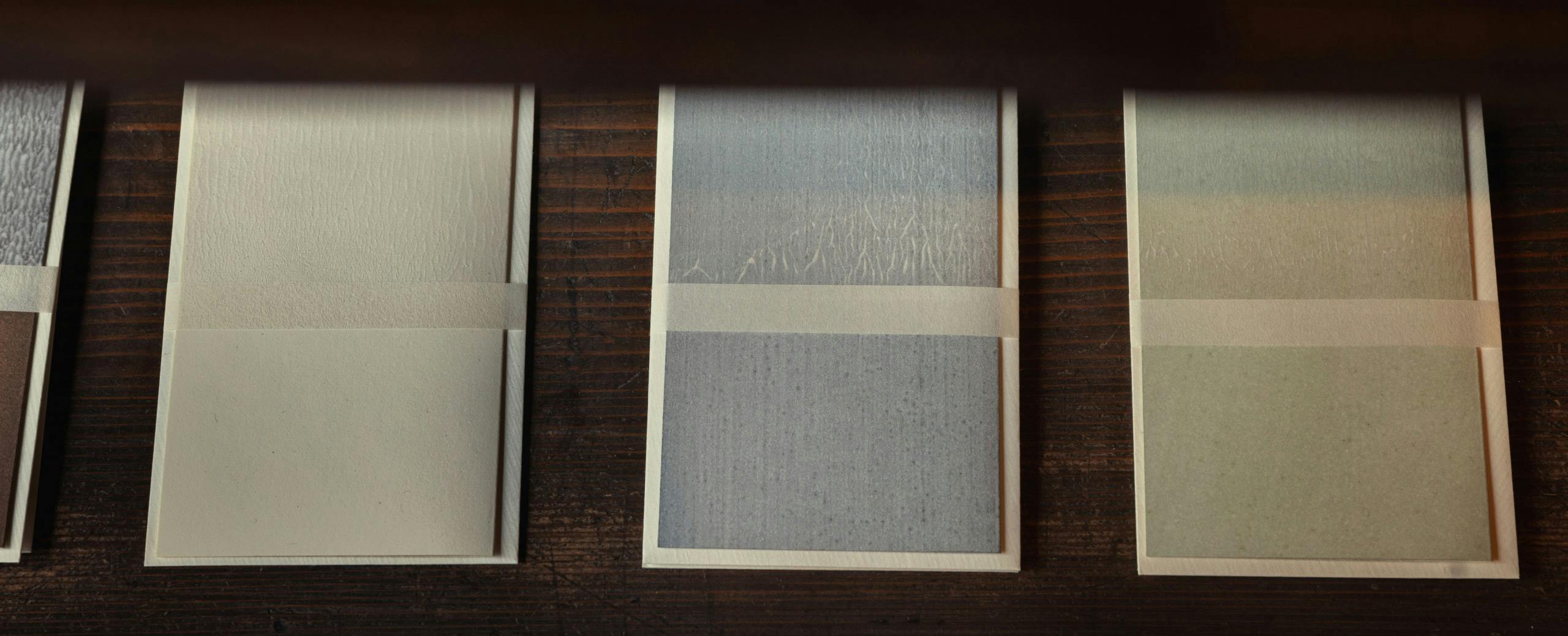

Located at the rear of the space, a narrow staircase provides access to the first floor, where Kado works with paper on a daily basis. Specialising in the traditional craft of ‘karakami’, his work involves dyeing paper and then applying patterns with woodblocks. The studio centres around a broad workbench, with rows of brushes lining the walls and printing samples arranged like a patchwork, catching the soft light filtering in through the windows.

Born and raised in Kyoto, Kado followed his own unique path into the world of traditional crafts. After studying graphic design at university in San Francisco, he ventured across the country to work as a freelance designer in New York. “I always used to love visiting printers and seeing them adjust their machinery and create special coloured inks. Within the field of design, I was more interested in the basics of printing, working with paper and creating colours, which eventually led me to karakami,” he explains.

Returning to his hometown, Kado joined a centuries-old karakami workshop, where he spent five years honing his skills and developing an appreciation for the traditional craft. He founded his studio and shop, Kamisoe, in 2009 and began working as an independent artisan. As time passed, he came to understand the influence of his design background on certain facets of his practice. “That experience shaped my way of thinking and looking at things,” he says. “The designer mindset really comes out when I am creating a shop space or displaying my work, but when it comes to designing patterns, I don’t think it has much of an influence.”

The history of karakami dates back to eighth-century Japan, when paper crafted in Tang China was used by aristocrats for writing letters and poetry. This lay the foundations for the production of Japanese-made karakami, which was later used to decorate ‘fusuma’ (sliding doors), folding screens and other interior surfaces. The technique gradually spread throughout society and has remained a feature of traditional architecture, while also being used in the creation of artworks, stationery and paper products.

Producing paper for projects ranging from world-class restaurants to boutique hotels and invitations for maison brands, Kado’s aesthetic draws on a natural palette, depth of textures and the subtle use of luminescence. Each original design is tailored to the project and created through a simple printing process. Dyes are prepared by hand using a mixture of pigments, minerals and ‘funori’, a natural adhesive. Echizen-made vellum paper is then dyed with a base colour, before a pattern is applied using a carved woodblock. Pressure is applied by hand to complete the print, before the paper is peeled back to reveal the finished design. Many of the tasks are undertaken by hand, resulting in subtle variations and imperfections.

“The culture of making is absolutely relative. The reason that handcrafts are now so prominent comes from the ongoing development of technology. Homogeneous versus non-homogenous, machine-made versus hand-crafted, mass-produced versus small-batch ... everything is relative, so both sides need to coexist,” he explains. “People often say that things can be copied easily these days, to which I say, ‘Go ahead’.”

“The more copies there are, the more desirable original creations will become. Things made by hand are essential – they’re like our heart and soul.”

When it comes to producing such things, Kado’s background and experience in entering the world of traditional crafts from the outside has shaped his perspective. “I wasn’t born into a family of traditional craftspeople, so I don’t feel too bound by traditions. There’s a certain sense of freedom, but I have a deep respect and admiration for such traditions,” he says. “When you’ve been doing something for centuries it becomes natural. There’s certainly some beauty in that, but coming from the outside, I view the past in a completely different way. That’s why instead of trying to do something new, I aim to find value in longstanding traditions, seeking out new and interesting ways to work with them.”

Through this process, Kado’s ability to examine and interpret the past forms part of his identity as an artisan. “I can’t just do anything, because going too far will end up ruining the culture,” he adds. “I have certain standards. I would never simply make a new copy of a classic pattern. Instead, I’d look to use the traditional techniques in a different way.” This philosophy can be seen in his approach to pattern design. Unlike other studios that may use woodblocks passed down through the generations, he creates original designs and commissions woodworkers to produce them. The inspiration can come from various sources, ranging from nature to the temples and architecture ingrained in his daily life, but most importantly, they are seen through his own eyes.

As a contemporary craftsman, Kado is constantly applying his techniques and expertise in a range of contexts. Even within the confines of Kyoto, his works can be witnessed in settings as varied as tearooms and temples, galleries and retail spaces.

For the Sabi tearoom in Gion, the late designer Taiga Takahashi tasked Kado with crafting karakami with an old, rust-like expression inspired by the walls of Tai-an, the sixteenth-century tea house designed by renowned tea master Sen no Rikyu. The artisan’s charcoal-dyed washi wraps around the entire space, from the main walls to the tokonoma enclave, with the ebbs and flows of each and every brushstroke soaked into each sheet. As the late afternoon sun descends, the wallpaper’s complexion shifts from charcoal brown through bronze and gold, painting a picture of transience. Finding harmony within the space, Kado’s creation links past, present and future, just as the designer intended.

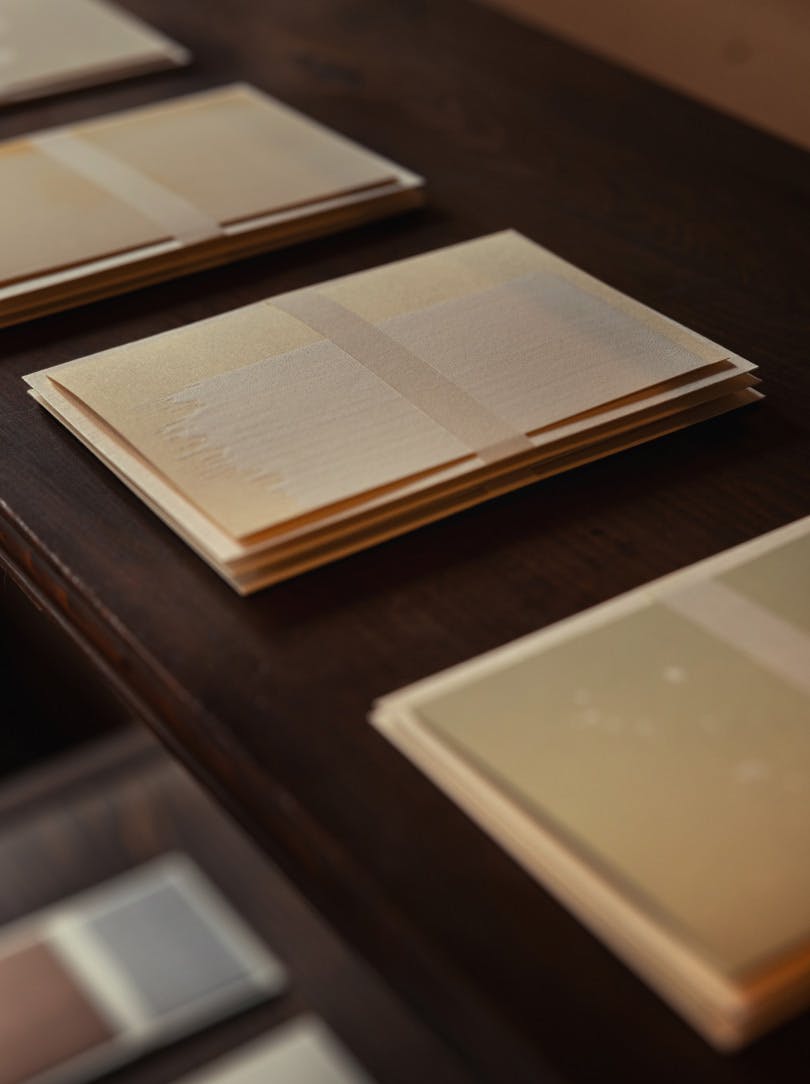

In late 2022, not long before Sabi’s opening, Kado presented a series of commissioned artworks and stationery for ‘Shiro to shiro’ (Blank and white), his first exhibition at Arts & Science. Building on discussions with the brand’s founder Sonya Park, he created all-white byobu folding screens based on two kinds of ‘shiro’ – the blank space of paper and the white of mica isinglass powder, an ingredient used in karakami dyes. Commenting on the exhibition, he said: “I think the existence of a blank space is a design element that you simply don’t notice unless you are conscious of it. The white space is more important than the main pattern, the space is more important than the karakami, fusuma, and the colours of the surrounding building materials is more important than the colour of the karakami. I feel that the balance of these surroundings creates the rhythm and atmosphere of a space.”

These fundamental concepts of space, balance, rhythm and atmosphere seem to permeate his works, whether it be byobu folding screens, rust-coloured wallpaper or minimal stationery. Standing at the entrance to Kamisoe in Nishijin, he reflects on his position in the field of karakami. “As a craftsman, it’s not good to be too focused on doing something new. At the same time, I don’t want to be as stubborn in my ways as the craftsmen of the past. I try to keep a balanced perspective, so while I’m grateful when someone sees something new in my work, it doesn’t affect me. The only thing that changes are my surroundings.”

A set of four white-on-white greeting cards designed exclusively for AGOBAY can be found in our shop’s permanent collection. We collaborate regularly on seasonal projects for limited edition pieces, so be sure to check in regularly to keep track of the artist’s latest works.