Listen

to Katherine Kennard

reading this story

Emptiness that fills you

Memories of Iceland

Seclusion, simplicity and tranquillity. Feeling nature without any distractions. Savouring the force concealed within its depth. This we wanted to experience and make part of our being. So, it beckoned us to the remotest corner of Iceland – to Hornstrandir.

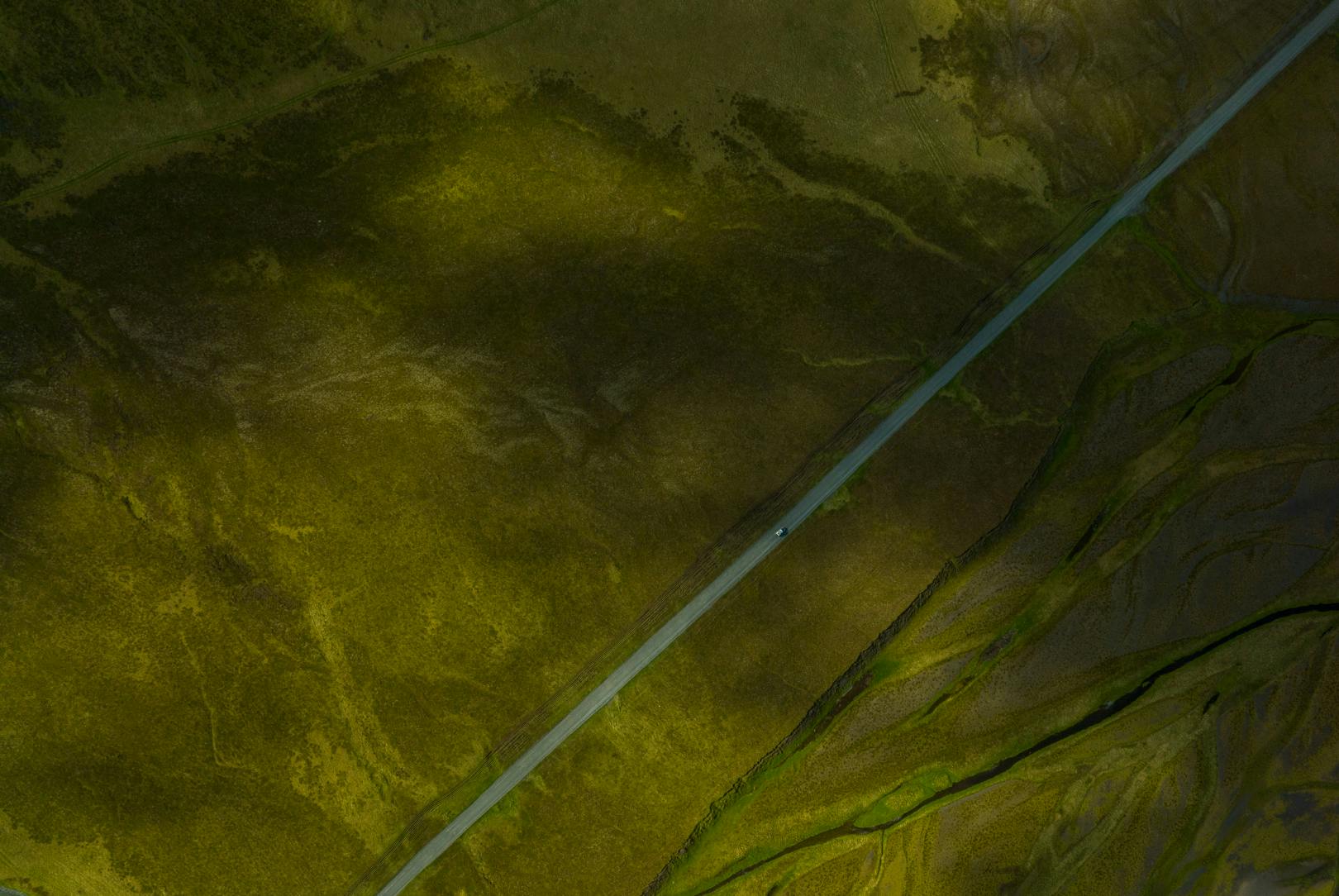

From Reykjavík, the road winds between the outstretched hills like a black snake. Fjords sweep past. The monotony of the landscape beguiles us and imparts a feeling of calm, of peace. We only encounter a few cars. Sheep graze by the wayside. Rain pelts the windscreen incessantly, all day long. But that doesn’t detract from the drive. The drops hit hard, then slowly, and gently roll down the side window, creating a meditative effect. Intuitively, we open the window and stick our heads out into the rain, feeling the freshness on our faces. Hurrah! We have arrived in Iceland. It feels good. The drive through the Westfjords to the north of the island gets us into the right headspace very quickly. Yet this is only a foretaste of everything we will experience in the coming days.

In Ísafjörður, a coastal village, a captain awaits us with his boat. To reach Hornstrandir, we have to leave our rental car behind; the peninsula is only accessible by boat. The sailor – a man of few words – tells us to come aboard. His skin is tanned by wind and weather – the legacy of a rough life. We are his only two passengers today. Not that he usually has many more.

On the boat, we sit down on the worn leather chairs and breathe in a mixture of salty air and the smell of diesel. It accumulates around us like fog. Maybe that’s why we doze off shortly after departure. We’re also lulled by the calm sea, which has no desire to fight any battles today, and the first gentle rays of sunlight that fall on our faces through the windows of the boat. Thus, we glide into the bay in the fjord of Veiðileysufjödauert. The journey doesn’t take much more than an hour, but it removes us far from everyday life or easy accessibility. Gone is anything that might impede our thoughts from slowing down. The next few days belong to us. The sole engagement we have is with the boat that is supposed to pick us up in another bay in five days. Our backpack contains everything we need to hike across the peninsula for several days.

After we arrive, we pitch our tent in the deserted bay. In short order, we site it behind a little knoll, protected from the wind, blow up our mattresses, put our sleeping bags on top, move the other luggage inside the tent and cook a small meal on our gas stove. Afterwards, we sit down on the stony beach and look out to sea. We take a deep breath, taking in the fresh aroma of herbs and grasses. We smile. A feeling of bliss takes over.

A multi-day trek on Hornstrandir

We wake up before the alarm clock can jolt us awake. Still sleepy, a glance out of the tent reveals that the weather is kind to us. The sun casts a glittering carpet on the surface of the sea. A few minutes later, a welcome sip of coffee wakes us up in earnest. The tent and all the other equipment go back into our backpack and we head uphill towards the Hafnarskarð pass. After a few steps, we near a rushing stream, where we fill our water bottles and savour the cold, fresh water. Wonderful. Spirits soaring, we climb, feeling the weight of our backpacks. On a snowfield shortly before the summit of the pass, we start sinking deeply and can only make slow progress. But the effort is worth it: the reward is great when we catch sight of the bay of Hornvík on the other side of the mountain. Weary, we sit on a large rock and look down to paradise.

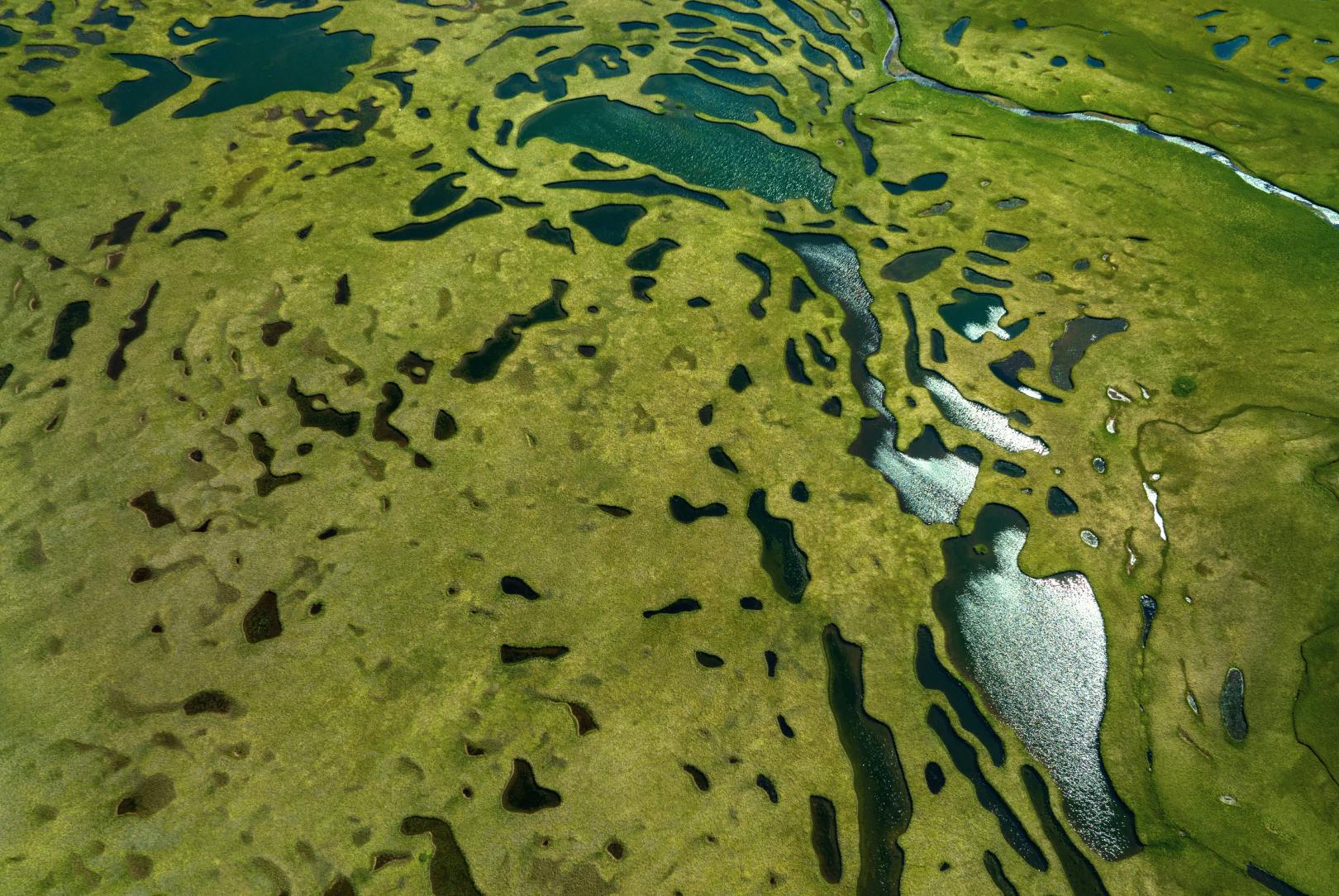

There’s no other way to describe this place. It’s as though we’ve happened upon a spot where man has not yet left any trace. Streams, little lakes, grassland and dunes paint a picture of perfection. Flocks of gulls fly over the plain and all kinds of wading birds settle here, among them golden plovers, sandpipers and redshanks. In Hornvík Bay we pitch our tent for the next two nights.

From here we go hiking on the bird cliffs of Hælavíkurbjarg and Hornbjarg, two of the largest cliffs in the North Atlantic, inhabited by around six million seabirds in the summer months. They nest on tiny ledges in the steep walls. Their cries echo far out to the open sea and their activity on the rocks is a theatrical spectacle, as they feed their young and defy the strong winds to wheel through the air with seeming ease.

The circular walk from Hornvík Bay to Hornbjarg, Hornbjargsviti lighthouse and back again takes us along spectacular cliffs. The flora is reminiscent of the Alps – wild thyme, lady’s mantle, buttercups and various roots grow along the path. While we walk, the fog begins to envelop the surroundings. Thankfully, it refrains from ascending to the plateau; instead, it blankets the sea below. As we’ve enjoyed two days of sunshine on Hornstrandir, feeling spoiled, we now brace ourselves to experience Iceland’s tempestuous side.

Calmness descends

There’s no point in leaving the tent. The rain pelts down heavily, unabated. It’s early morning and we’re keen to start hiking, but instead we remain within our four-square-metre shelter. We listen to the raindrops bouncing on the tent, by turns dully or playfully, sometimes sounding like a leisurely, strolling gait, then as though they’re sprinting. They seem to want to tell us stories through their rhythm and intensity. When the rain becomes quieter, we hear the thunderous roar of the nearby sea. The temptation to leave the tent and take in nature is growing; after all, that’s what we’re here for. But the warm, woolly sleeping bag and dry clothes are a good counterargument, so we hold out.

Towards noon, the rain finally begins to let up. We decide to take down our protective tent and start hiking. The first half hour takes us along the coast. The cool wind has an invigorating effect. Walking along the coast, with its slippery rocks and sharp edges, is an arduous business, not least because it requires concentration. It is then that we realise that something is happening. After two days, our minds are quieted. We are only mindful of what is happening around us. All brooding, ruminating or daydreaming has disappeared, leaving a deep sense of satisfaction in its place. In this moment, it’s as though we’re on pause. We return to this state over and over again over the next few days, sometimes for brief periods, and sometimes longer. The trigger is silence and the absence of constant stimuli. In our everyday lives, we have become accustomed, perhaps overly so, to being constantly interrupted by our digital aids. Our minds whirl with thoughts, one after the other, and compounded by myriad feelings. We have strewn our world with distractions and eliminated boredom from our lives. But here, in this deserted expanse, this privilege rekindles our happiness. The beauty of it all is that you need not seek this state, it simply finds you. You just have to provide it with the foundation. Peace. Silence. Simplicity. Hrólfur Vagnsson also talks about this at the end of our five days on Hornstrandir. The musician spends the whole summer on the peninsula. He tells us that there’s nothing more beautiful than hearing nothingness.

In the bay of Hlöðuvík, we come across a small homestead. It bears witness to a time when people lived year-round even in the remotest places on Hornstrandir. As farmers, they earned their living away from civilisation. A local tells us that his grandfather once lived here. Today, he and other family members use the farm for their holidays. Then he laughs and points up to the mountains, saying, “If my grandfather needed new tobacco for his pipe, he had to walk to Hesteryi.” Next day, we find out how far away Hesteryi is – once the largest and most populous town on Hornstrandir, it is now our destination, too.

Arrival at the Old Doctors House

Today’s hike takes us over a pass to Hesteryi. Often the paths are hardly visible. Thick fog surrounds us, but there’s little rain. Yet now the weather has been consigned to a secondary role. Our days of quiet have filled us with a sense of lightness. Being far away and disconnected from the usual noise brings joy to the little things. Even crossing a stream feels wonderful – if you can reach the opposite bank dry-footed by playfully hopping over the stones. So does the sight of a few doughty pink or yellow flowers in the barren scree landscape, defying the dreariness of their surroundings with their colourful dress. The giant cairns are a sign of solidarity, showing us the way every few hundred metres. We thank the hikers who passed through here before us by adding a stone or two of our own. After six hours we glimpse Hesteryi, a collection of modest houses by the sea. On the outskirts is our accommodation for the coming night: the Old Doctors House.

Here we meet Hrólfur Vagnsson, our host. He welcomes us with a warm yet reserved smile. Shoes off, wet socks over the heater, we sit at a wooden table, look out to sea and drink a cup of coffee. It comes with a cinnamon bun. The sparse cress growing next to a little vase of wild flowers on the windowsill reflects the luxurious status of things here that we usually take for granted. Apart from the fish served in the evening, everything has to be brought to Hesteryi by boat. And not just food – the wooden table and even the house, as there are no forests on Hornstrandir. Hrólfur Vagnsson explains: “The Old Doctors House, like many of the houses here, is a prefabricated house from Norway”.

The history of Hesteryi is closely linked to a factory whose ruins are 20 minutes’ walk from the village. It was built around 1900 as a whaling station. Due to the factory, the village grew from a few families to about a hundred people. A community was formed, and it needed a doctor and a school. As a result, the first doctor moved to Hesteryi in 1901. Whaling was banned in Iceland in 1915, but the factory remained and served as a herring factory. The Old Doctors House, as it’s called today, was the doctor’s house. One room in the house served as an infirmary for patients who had to spend the night here. There were also treatment rooms, a waiting room and a pharmacy where the kitchen is today. Our host recalls: “When we came here as children, the house no longer served its original purpose, but it still smelled strongly of a pharmacy.”

No one has lived on Hesteryi all year round for a long time now. In 1940, the herring factory closed because the large shoals of herring were overfished and were moving further east. Most of the workers left the island. The doctor and the school closed their doors two years later. Finally, in the spring of 1952, the last 18 remaining residents met and decided to stay in Hesteryi for one last summer, after which they too left. No one has lived here permanently since autumn 1952.

A café at the end of the world

In 1994, Hrólfur Vagnsson’s mother bought the former doctor’s house. It allowed her to realise her long-cherished dream of opening a small café. “Back then, maybe fifty people a month came by,” says Vagnsson. “There were hardly any ferry connections to Hesteryi.” Iceland received relatively few tourists in general. Vagnsson himself was living in Germany at the time, studying music and working as a recording manager. In 2006 he finally spent his first summer in Hesteryi and for the last five years has been running the Old Doctors House on his own. His mother is now 90 years old, “but she ran the café with complete dedication until she was 85,” says Vagnsson.

Nowadays, Hesteryi is served by boats daily during the summer months. Most visitors stay for a few hours, take short walks and stop at the Old Doctors House. If you’re lucky, you can spot arctic foxes here. They lived in this area before humans did and are protected.

Hrólfur Vagnsson comes to Hesteryi in April or May and stays until autumn. He spends the winter in Hamburg. The peace and silence are an important part of what draws him to Hornstrandir. “I work with music, where silence is just as important as sound,” he says. And then he says something that resonates with us for a long time: “There’s nothing more beautiful for me than to hear nothingness.” He goes on to speak of his perception of individual sounds, images and smells. “When I’m here, I can concentrate on the song of a single bird or the murmuring of the brook.” There’s great strength in that, he says, “There’s nothing happening on Hesteryi, yet there’s always something going on.” You can sit at the window, sometimes for hours, and look out over the fjord. You see the same fjord over and over again, but it’s a different picture every time. “When a boat arrives and moors 300 metres away, if the wind’s blowing in the right direction, I can smell the diesel here. In Hamburg, you’re always in the middle of hundreds of cars, so you stop noticing things like that.”

And that’s what happens: we smell the diesel. In truth, the hum of the engine reaches us first. Our boatman has kept his word and picks us up after five days. We get into our hiking boots, which are dry again, shoulder our backpacks, board the boat and leave the Hornstrandir peninsula behind us. A wistful look back prompts a thought: are we actually leaving Hornstrandir? Or has it taken up residence within us?

Does it exist in a corner of our minds, a place close enough to what makes us tick that, when we return to our hectic everyday lives, it can call out to us every now and then, “Relax. Let go.” Or perhaps it resides somewhere close to our hearts, so that it can warm us with memories of the joyfully dancing rain, the paradisical bay of Hornvík, sweeping views of the sea, deep conversations, lightness and light-heartedness. Memories of Iceland.