Play Movie

Listen

to Katherine Kennard

reading this story

A HARMONY OF ARCHITECTURE, SOUND AND STILLNESS

Slowness’s Reethaus

As we approach Flussbad from the busy dual carriageway that cuts through the east Berlin neighbourhood of Rummelsburg, divided by tram tracks and running parallel to the River Spree, the industrial presence of the area hangs in the atmosphere. Glimmers of sunshine break through the clouds as we walk along the wide pavement that borders this arterial road, alongside which a high brick wall stretches into the distance, plastered with a seemingly endless array of large colourful concert posters and fashion advertisements. We pass the bronzed gates of Sisyphos, an open-air techno club housed in a former factory. The distinctive white chimney tower of the 1920s Klingenberg Power Plant looms ahead. We have arrived.

The industrial feeling lingers upon entering through the open campus gates and facing a somewhat imposing brick-and-glass building, several storeys high. But this begins to dissipate and morph into something decidedly more contemporary as we move inside, ring the doorbell marked ‘SLOW’ and are warmly greeted with a smile by one of the understatedly stylish employees. Flussbad is the campus of Slowness, an experimental hospitality collective that aims to reframe the way we live, work and come together, co-founded by industry vanguard and visionary Claus Sendlinger and consultancy mastermind Peter Conrads.

Stepping inside, it’s almost as if another dimension opens up before us: expanses of polished concrete floors, walls and ceilings, which are vaulted with broad concrete beams. A smattering of well-placed spotlights gently light the space, along with today’s soft natural light flowing in through large windows on either side. Rather fittingly, time slows, a quietness pervades, and our senses become heightened as we explore these rarefied surroundings.

The office is sparsely furnished, but every piece has clearly been carefully chosen for its simple beauty and function. Japanese-crafted wooden chairs and stools create elegant shapes against darker timber tables – a higher one, with just an Ikebana-type arrangement in a vase placed on top, and a lower, elongated one forming the desks and main working area. No clutter is to be seen.

The most detail is on an artfully curated moodboard featuring beautiful images of all the Slowness projects. These include Slow Wonder in Thailand, comprising 26 cabins and an Ab Rogers-designed restaurant in collaboration with the culture and music festival Wonderfruit; the craft bakery Sofi, set in a tranquil courtyard in Berlin-Mitte, which focuses on low-intervention baking using ancient grains; and the 114-hectare farm Herdade do Meco, in Portugal, an initiative to regenerate soil and cultivate a community, featuring a restaurant, farmhouse, cabins and private housing. Highlighted on black wall panels at the far end of the room, the moodboard is a natural focal point, benefitting from the light cast through the adjacent expanse of floor-to-ceiling windows. This stark minimalism, however, is not at all stiff or formal, but rather serene and calming.

Gazing through this wall of glass, we see the wide terrace, and beyond it a far-reaching view of neatly contained wild greenery all the way to the river. The domed thatched roof of the Reethaus, a performance and cultural space for art, music and contemplation, also gently comes into view, but it is so subtle that it looks like part of the natural environment, like it has always been there. A deep sense of what this place is begins to bloom: a lush urban sanctuary where the frenetic energy of the city gives way to an immersive stillness.

Only three or four people are in the office today, as an event is taking place later and most employees are busy preparing for it across the campus. Claus Sendlinger suddenly appears from behind an enormous single-panelled concrete door that pivots in the middle, his presence at once commanding yet also warm and approachable. Dressed in a cotton utilitarian-style shirt and matching trousers in the darkest navy imaginable, with navy socks and smooth, soft-looking black leather loafers, the Slowness co-founder greets us, smiling, with arms outstretched for a friendly hug. He has a thick grey beard, a textured mix of light and dark, luminous light blue eyes and an easy manner that makes us feel like we could be old friends. It’s no wonder he is a pioneer of the hospitality industry.

“I feel good here. I think it has a great energy. And this isn’t about me, it’s very much a collective exercise here. That alone is something beautiful.”

CLAUS SENDLINGER

Following some discussion about where best to sit and talk quietly, Claus politely ushers us back into the austere entrance hall and up two flights of stairs to a door marked ‘PAD’ – his onsite studio apartment where he stays when not at home in Lisbon. An incredibly soothing, delicate scent fills the air of his “crash pad”, as he describes it; he never stays here for long. Like the office, it is minimally furnished, decorated with purpose but also comfort, like a hotel room you don’t want to leave. Over small cups of Greek mountain tea and fragments of dark chocolate, we begin chatting about the energy of the place. “I love all these buildings,” Claus says. “I feel good here. I think it has a great energy. And this isn’t about me, it’s very much a collective exercise here. That alone is something beautiful.”

The site has a fascinating history as a public bathing spot known as Die Alte Flussbadeanstalt (‘Flussbad’ meaning ‘river bath’), when it used to welcome up to 10,000 visitors a day. Claus explains: “A hundred years ago, after the First World War, there were sanitation problems. Many didn’t have a bathroom. There’s this Kraftwerk, this power station, just across the street. In those days, coal was burned to generate electricity, driving huge turbines. Water from the river was used to absorb heat from the steam in the condensers. Then the warm, uncontaminated water came through pipes back into the river. They put in a huge swimming pool to make use of it, which was really just a wooden platform floating in the river.”

After the Second World War, Claus continues, the area served as the port authority of East Germany, but when the Berlin Wall came down, the whole area was abandoned. “In the mid-2000s, the former mayor, Klaus Wowereit, famously said, ‘Berlin is poor but sexy’. The city had no choice but to sell off property, including this site. It became an international bidding contest, he describes, and a friend of his won the bid. “He then approached us, as we had done some other projects here in Berlin and in Mexico, and he said, ‘I would love to do something like this. Could you come? Would you like to help me to put a team together?’”

“We wanted to create an inner-city retreat, a place where people could step out of the noise and reconnect with themselves, but without having to leave the city.”

This was in 2014. Claus was all in, and the more time he spent among the greenery by the Spree, right where it opens out into a 1km-wide point, the more ideas he had. “We wanted to create an inner-city retreat,” he explains, “a place where people could step out of the noise and reconnect with themselves, but without having to leave the city. That’s when we started to think about a campus.”

Currently, Flussbad is made up of the Slowness offices and headquarters, as well as the Reethaus, which opened in 2023, marking the first phase of the campus opening. It will continue to grow over the coming years to encompass hotel rooms, working lofts, ateliers, a restaurant, an auditorium for learning and exchange, and an advanced holistic health programme, including a longevity lab, spread across the campus. Much construction is already underway, as we witness today.

At the heart of this campus, and open to the public, stands the Reethaus, a structure so singular that it defies simple classification. Not merely a building, it is more akin to a living sculpture, an acoustic sanctuary and a space for radical presence. Claus speaks of the Reethaus with reverence: “We wanted to create a space that could stand at the intersection of architecture, art and sound. A place where people can come to listen, not just with their ears, but with their whole bodies.”

The Reethaus was conceived as a feminine counterbalance to the more masculine, concrete structures that already populated the campus. After much careful consideration, Austrian architect Monika Gogl came onboard to mastermind the building, for which she drew inspiration from natural forms, with soft curves and a flowing shape that mirror the water and landscape. “We wanted a structure that didn’t just blend into its surroundings,” Claus says, “but that became part of them. Something that felt organic, almost like it grew out of the land itself.” It took a year of trial and error before a design emerged that struck the right note. “Monika presented it to us, and we said, ‘Wow, this is amazing’,” he recalls enthusiastically. “It was a cave, it was a hole, it was a dome – it was exactly what we were looking for.”

This vision extended to the choice of materials, with a thatched reed roof being one of the defining features of the Reethaus. A traditional roofing material rarely seen in modern architecture, thatch was chosen not only for its aesthetic qualities but also for its deep historical roots in the region. “Our dream was reed,” Claus reflects. “Reed was used in this part of the world for centuries – for summer houses all round the Baltic Sea and in Brandenburg. It has this incredible organic quality that softens the structure.”

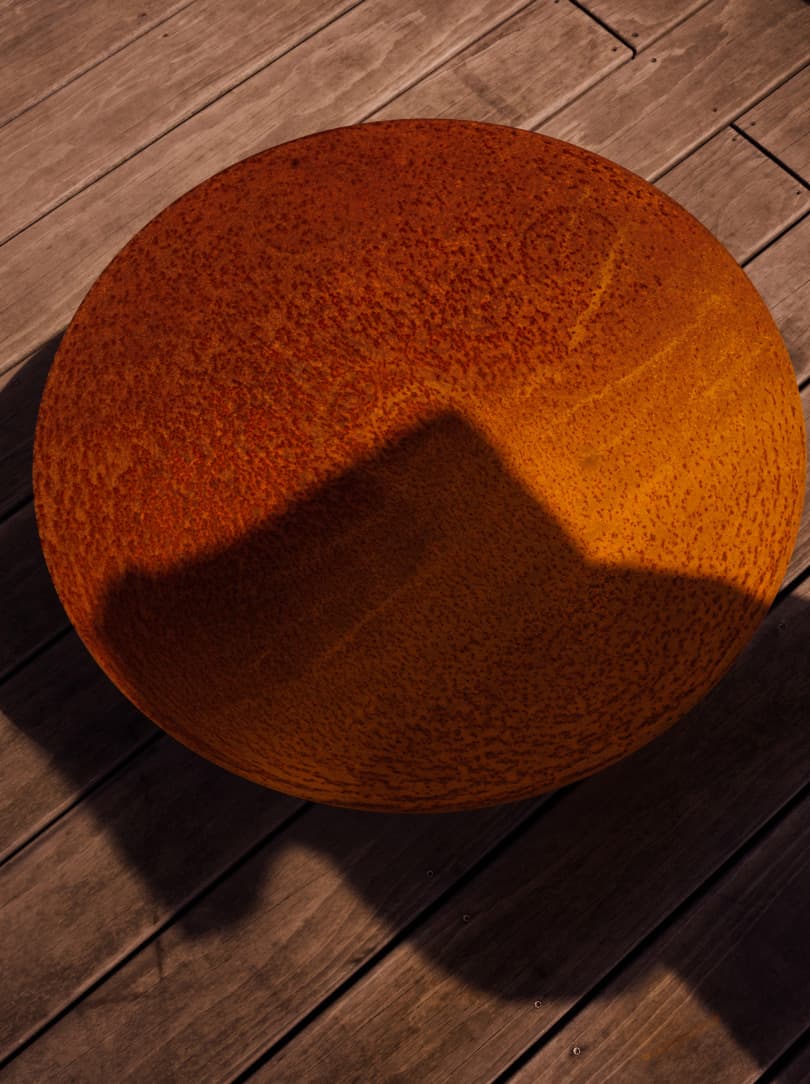

Claus and his team had to book one of the two remaining thatch artisans in Germany 18 months in advance. “And because it’s not a normal roof,” he explains, “all of the tools had to be individually made. We hope that it will give this industry or these crafts a new purpose, and that more people will visit it and consider building their own roofs with greenery.” The result is a roof that is ageing gracefully, taking on the elements and developing a patina that further integrates the structure into its environment. The architect also chose concrete as a primary building material, but applied the Japanese technique of creating a wood-grain imprint on the surface using rough-sawn boards of Tyrolean spruce. “Now the concrete looks like wood,” says Claus. “Many people are surprised when they touch it.”

While the Reethaus’s exterior is a testament to materiality and form, its true magic lies within. Claus invites us on a tour. Together, we leave the office building, crossing the wide terrace with its pared-back tables and chairs by Danish designer Frederik Fialin, and go down a few concrete steps to a wooden path, reminiscent of a seafront boardwalk, lined with verdant wild shrubbery and saplings. Turning a corner onto a broad concrete ramp, we gradually descend to the main entrance of the Reethaus, gaining a closer, more detailed view of the thatched roof as we do so. Once through the heavy double doors, we pause, blinking, to take in our surroundings. Ahead and to our left, wide empty corridors with polished timber floors head off in different directions. As Claus described, the walls and ceilings appear like pale panelled timber, too, and we feel compelled to reach out and touch it – it is definitely concrete, but a thoroughly convincing trompe l’œil.

There is a sense of anticipation and excitement, similar to arriving in a theatre. We walk the length of a corridor and realise it loops around an inner room. A skylight also outlines this room all the way round its exterior, offering an intriguing view of the blunt bottom edge of the reed roofing. At either end of the back corridor – which opens out onto a riverside terrace surrounded by abundant greenery, the tops of bobbing boats visible beyond the rushes – lie two spacious rooms, one with a beautifully simple conference table and chairs designed as a collaboration between Japanese lifestyle brand Karimoku Case and Danish design studio Norm Architects. In a small sitting area, there is a modular arrangement of low tea tables made from compressed burnt cork by Antwerp-based master of stillness Cédric Etienne, who created them especially for the space, along with tatami mats, cork-filled cushions, cork blocks and modern church-like pews. A few staff members move about gracefully in preparation for the afternoon’s event, wearing bespoke uniforms created by Greek fashion designer Kostas Murkudis. Claus’ aesthetic and philosophy are reflected in the brands he chooses to work with, carefully selecting them to ensure a good fit. We pause, again, to admire an inner garden, open at the top and with glass walls featuring a single white birch tree, before finally being ushered into the inner room of the Reethaus. We are struck by its simple splendour – high vaulted ceilings leading up to a multi-pane skylight, rows of pews by Cédric Etienne, softly rounded corners. In an instant, we know that this is a place where the senses come alive.

The building was designed not just as a visual experience but as a sonic one, too. Claus undertook thorough research on spatial sound to ensure that the acoustics of the Reethaus would offer something entirely unique. “The Reethaus is not just a space for listening,” he explains, “it’s a space where sound can move. It’s spatial sound – frequencies and notes can travel around the room, creating an experience that is both deeply emotional and transformative.” Claus pauses, then asks us to “imagine a buzzing bee, flying from the top to the bottom.” He extends his arm to demonstrate its path. “You would try to see the bee, try to follow it with your eyes, but you won’t see it, because it’s a sound. This is how, in very simple terms, spatial sound works.”

“The effect of spatial sound on the human body is that you’re not listening with your ears, you’re actually listening on a cellular level.”

The architecture itself amplifies this effect. Collaborating with sound engineers, the team fine-tuned every corner of the space, ensuring that sound wouldn’t just bounce off the walls but would flow through the room like water. Claus recounts the process: “We simulated how different frequencies would behave in the space – classical music, electronic music, even spoken word. It all had to work within this building.” Finally, the Australian-born, Berlin-based pioneer of spatial sound, and founder of MONOM, William Russell brought it to life. Along with his team of sound engineers, he now works with the featured artists to spatialise their work. And, together with the contemporary sonic arts platform Soundwalk Collective, founded by artist Stephan Crasneanscki and producer Simone Merli, they co-curate the programme.

The result is a space where sound isn’t merely heard, but felt. He describes it as emotional, saying people often begin to cry very quickly. “The effect of spatial sound on the human body is that you’re not listening with your ears, you’re actually listening on a cellular level, because the frequency hits you from everywhere in your waters. Our bodies start to adapt to that frequency. It’s very, very powerful.”

Later in the afternoon, having joined Claus for lunch in the office, we return to the inner room of the Reethaus to experience the preview of a site-specific audiovisual installation by an artist collective. Silently taking our seat on one of the elongated black pews, we focus on the large screen that sits on the floor in front of us. Drone footage of a body of water in Lithuania fills our vision while a dramatic polyphonic soundtrack plays out. We recall something Claus said earlier about how lying down with your eyes closed was probably the best way to gain full immersion into spatial sound: “It’s not psychedelic, but you’re reaching extraordinary states of mind. It can help with problem solving, it can build creativity, it can change the conversation.”

The Reethaus is also the physical embodiment of Claus’s broader philosophy, encapsulated in his latest venture, Slowness. Embracing the slow movement and seeking to build a collective of like-minded people, he advocates for a lifestyle that prioritises intentionality, presence and a return to simpler rhythms. It was a philosophy born from Claus’s own personal journey, one that began long before he became an industry leader in hospitality.

Born in Augsburg, Germany, in 1963, Claus grew up surrounded by nature, spending his days playing football on a riverside pitch (he later almost went professional), and playing in his father’s toy store. “I had a very humble upbringing,” he recalls, “but it involved many rituals, especially around food and hospitality. My mother loved to cook and host dinners, and was incredibly meticulous about decorating the table beautifully – there were always menu cards, and a starter, a main course and a dessert. That attention to detail stayed with me.”

The family’s annual holiday to the same hotel in Italy was also a formative experience. As an only child, Claus delighted in summers spent with the three sons of the hotel owners, with whom he learned to speak Italian. After leaving school early, due to poor academic results, Claus joined the air force, where he unexpectedly ended up studying communications and PR. This, along with a developing passion for travel, led him to later buy a travel agency and combine it with event production. It was a trailblazing move at the time, and he became one of the early electronic music event producers in Germany.

Eventually, in the early 1990s, he launched a curatorial platform called Design Hotels as a response to the hospitality industry’s failure to adapt to the changing tastes of travellers. “Back then, hotels were all the same,” Claus explains. “They were formulaic. But the new generation of travellers didn’t care about star ratings or luxury for luxury’s sake. They wanted experiences.” His knack for identifying what people wanted before they even knew it themselves made Design Hotels a global success. “We weren’t just helping sell hotel rooms, we were selling an idea – a way of living. And that feeds into Slowness as well.”

Claus counts resilience and a keen awareness for detail as personal attributes that got him to where he is today. That, and discovering the joy of slowing down. A sabbatical in Mexico became a turning point. “I went to Mexico for six months and ended up staying for six years,” he says with a smile. “It was there that I began to understand the value of slowing down. Living on the beach, going to bed when the sun set and rising with it – I started to see how much more present and alive I felt.”

“It’s a space where people can come, slow down, and really listen to themselves, to the world around them and to the music of life.”

Slowness, Claus continues, is not just a business, it’s a movement, a way of life. The Reethaus is part of that movement. “It’s a space where people can come, slow down, and really listen to themselves, to the world around them and to the music of life,” says Claus. In fact, all of the Slowness projects embody this, offering not just a ‘pit stop’ away from the hectic pace of daily life but a continuous journey of reconnection, the latest of which is Casa Noble, a small hotel housed within three different historic buildings in Lisbon’s ancient Graça neighbourhood, due to open in the latter half of 2025.

As we leave the Flussbad campus, the serenity of the space lingers. The Reethaus, with its graceful curves and immersive soundscape, is a reminder that in a world that is constantly speeding up, there is still a place for slowness. And in that slowness, we can find not just respite, but renewal.