Play Movie

Listen

to Katherine Kennard

reading this story

ALCHEMY OF INDIGO

Tian Taru

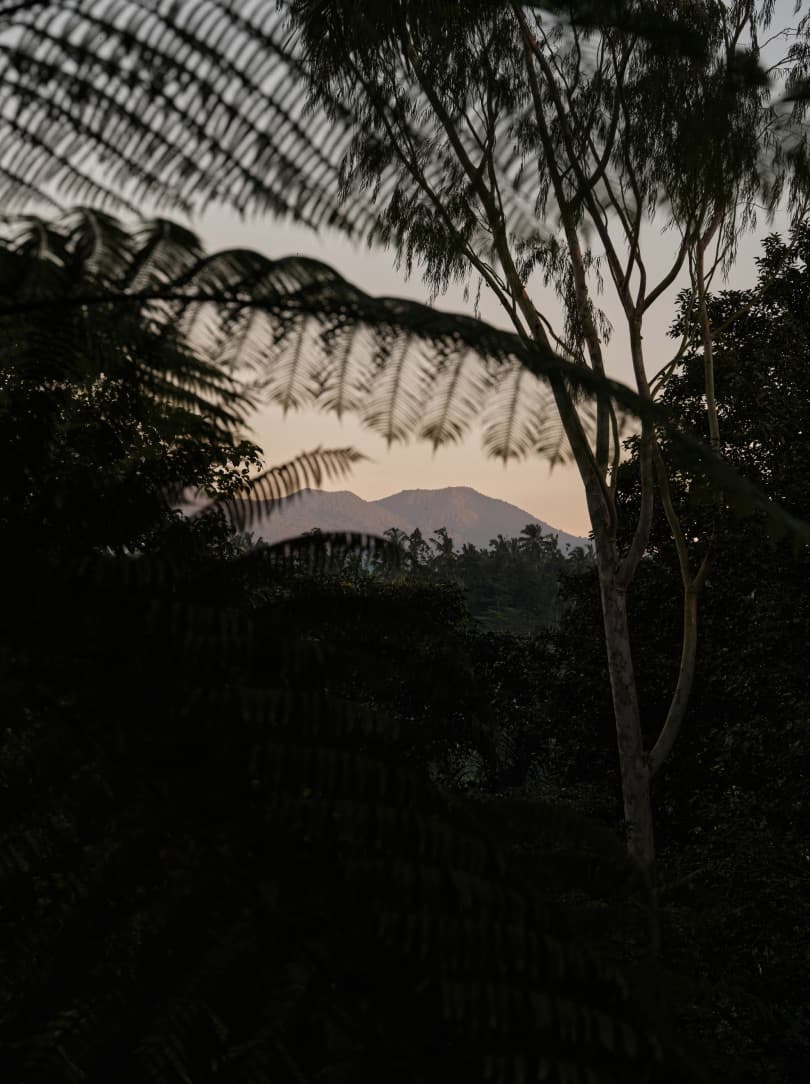

In the half-light of dawn, the contours of Gunung Batukaru begin to reveal themselves to us. Below this celestial mountain, a vast expanse of tropical forest swells with a morning chorus of birdsong and trilling frogs, punctuated by the crows of a rooster. Mists linger in the steep valley where waterfalls pour into streams studded with mossy boulders. Above, swallows twirl circles through the slow-blushing sky. Even on the cusp of the dry season, mornings are crisp in Payangan, an agricultural district in Bali’s Gianyar Regency, veined by curling, jungle-fringed roads that stretch north of Ubud to an elevation of 700 metres above sea level.

As the mountain ridge is warmed by the sky, soft light illuminates the simple room in which we awaken, hand-built from ironwood and teak and harmonious in its solidity. To welcome the day as a guest at the indigo plantation and dyeing studio of Tian Taru is to unwind into a way of life far removed from cosmopolitan rhythms. It is to be immersed in a forest cultivated with care on what was a barren rice field only twenty years ago. It is to witness the realisation of an artist’s dream: the desire to rekindle a childhood lived in nature, feet bare and mind free. Above all, it is to be welcomed into the home of a family woven together by a love story forged against the odds: Ayu Purpa and Sebastian Mesdag, their daughter River and their son Tian, whose name is combined with the Balinese ‘Taru’ (tree) to make ‘Tian Taru’, meaning ‘the tree that grows between heaven and earth’.

Signs of life stir with the lifting light outside the simple room we’ve awoken in – a multi-purpose space for plucking indigo leaves and hosting guests who stay for private indigo dyeing workshops. Framed by tree ferns, a path curves towards a two-storey family home, where smoke hazes from the orange blaze of a fireplace before which a cat, the three-year-old Kala, is stretched. At a round table, Ayu, Sebastian and their two children gather for breakfast. River, nearly as tall as her father, is radiantly warm, with rippling dark curls. As she chats in her international lilt with her younger brother Tian – expressive with a cheeky glint in his eye – their parents exude calm. Ayu is as softly spoken as her presence is magnetic. Her dark gaze continually observes, present yet apart. She wears her long black hair clasped back, revealing small gold hoops in her ears, and a loose white linen shirt.

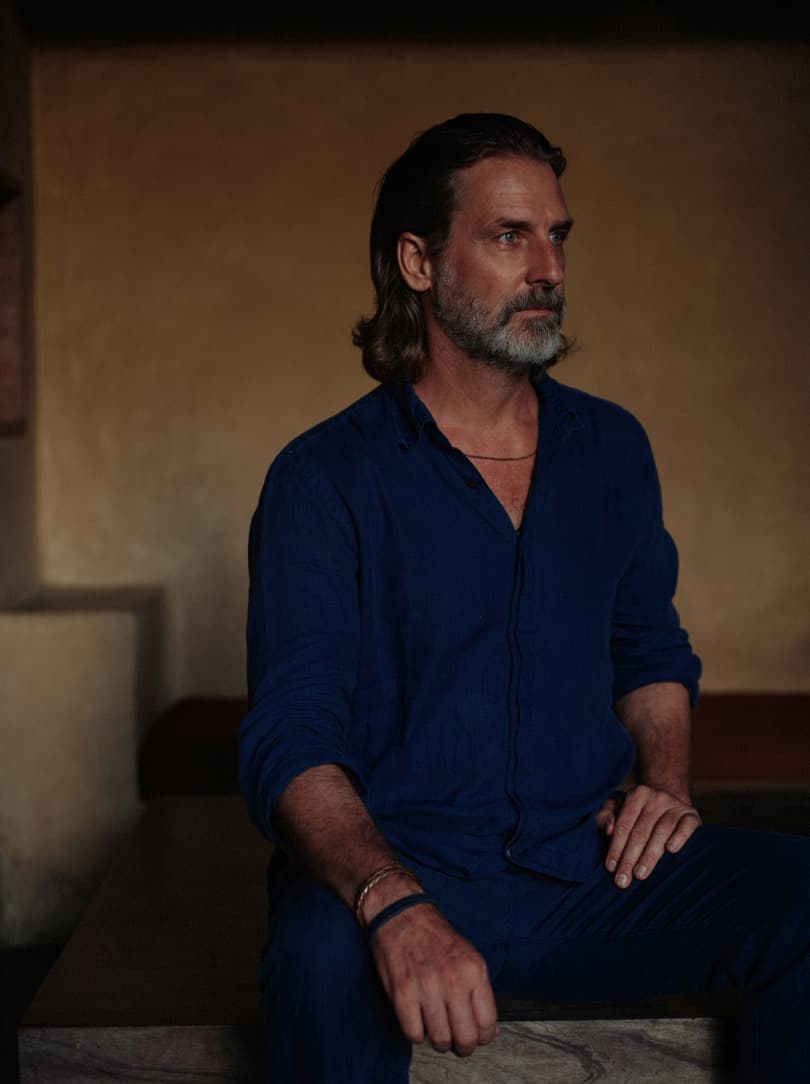

Honey-blonde Sebastian – known to his nearest and dearest as Seba – is tall, with impeccable posture. He is quick to laugh, the sparkling blue of his eyes accented by the radiant blue shade of his shirt. His demeanour is that of someone at ease outdoors. Always barefoot, he appears to glide over the land, the bottoms of his jeans seemingly repelling the ground’s residue. He often leaves his wire-framed reading glasses behind.

Around his feet, Bantam chickens with gemstone-hued feathers chase each other across the lawn, impervious to the gaze of the three dogs observing them from the porch: silky grey Baru; golden-haired Lama, a cross between a Rottweiler and a Kintamani rescued from the street; and sprightly Lima, the “lady of the house”, as Ayu says. A regal peacock makes an appearance, scattering the chickens in its wake.

The family are soon joined by their team of indigo harvesters and dyers, Ibu Kandri, her daughter Ibu Putu, and Ibu Komang. They move slowly and purposefully, bringing the corners of the property to life. Resplendent in a scarlet sarong and purple-toned shirt cinched with a fuchsia tie, Ibu Kandri, who was born on this land and still lives here in a simple Javanese wooden ‘Gladak’ hut, prepares ‘banten’: traditional Balinese offerings meticulously prepared to express gratitude and seek blessings. Plumes of incense billow from baskets heaving with jewel-like flowers, dragonfruit and mangosteens in a deep, rich purple as she carries her tray up to the temple overlooking the indigo plantation. There, she releases a silent prayer before delivering a second offering to the indigo studio.

In the open kitchen, chef Dayu begins to prepare ‘jamu’, a herbal tincture made of fresh turmeric, ginger and tamarind paste infused with palm sugar and lime, ready to offer to workshop participants on arrival. Lemongrass, chilli and herbs plucked from the property that morning are worked into Urap pakis, a fern tip salad with grated coconut, and added to chunks of tempeh. A freshly caught fish has been delivered by Pak Andika, Sebastian and Ayu’s partner at Tian Taru, who arrived with his colleague to prepare the vats the night before from Singaraja, a remote coastal region two hours to the north. There, Pak Andika runs his own natural dyeing studio and workshop, Pagi Motley, where indigo is just one of several colours in his palette. Together, the duo carries large vats of indigo dye onto the grassy lawn. Perched on child-sized chairs, they begin to activate the oxidation process, scooping sheets of thick turquoise water out of their tub with coconut shells.

The plant that gives the liquid its colour has an ancient history shrouded in mystical paths that lead through the Asian, African and South American continents. Its oldest known application in textile colouration is believed to be a 4,000-year-old piece of fabric from Peru, on which traces of indigo were found. One of the indigo plant’s many varieties is Assam, which is thought to have originated in the eponymous north-eastern Indian state. From there, it travelled to neighbouring Bhutan, through to Japan, and into Vietnam. It came into Sebastian’s hands in the form of three small cuttings gifted by a friend familiar with his love of natural dyeing and trees. “I planted them and then forgot about them,” Sebastian says. A few months later, when he happened to check on them, he was taken aback by how fast the plant had flourished. “We started propagating it when we saw that this was the perfect climate and the perfect area for it to grow.”

Whether fortuity or fate, an element of chance has shaped not only the arc of Tian Taru, but also the love story on which it is founded. It begins in two distinct places. In central Ubud, Ayu, a twin daughter of a jeweller, grew up among rice fields, catching dragonflies along the river in the evenings. When she was 19, her village priest shared a prophecy with her: when Ayu would eventually meet her husband, they would live together in a remote location and do something together; something that people would be interested in coming to see. “When I remembered that moment, I sat down,” Ayu recalls. “I was like, ‘Wow, maybe this is what the priest meant. I’m not sure if it’s because I believe what he said, but I feel it’s destiny that I met Sebastian. I wasn’t looking for him. It just happened.”

Across the world, in “the middle of nowhere” in Andalusia, Spain, Ayu’s future husband was growing up on a farm surrounded by sugar cane, horses, chickens and dogs. He and his three siblings addressed their parents by their first names, and referred to the farmer and shepherd with whom they shared the property as ‘Papa’, so close was their connection. While not tending to the land, the family, whose roots are Dutch, travelled. When Sebastian was 14, his family went to visit his uncle, who had moved to Bali in the 1930s, where he ran in the same avant-garde circles as German artist Walter Spies. At that point, Sebastian recalls, cars and even motorbikes were rare on the island. “They’d just opened Casa Luna, the first bakery. You could suddenly buy yoghurt and a few Western things.” Throughout his youth, trips to Indonesia became a regular occurrence, leading him to the first piece of indigo-dyed fabric that would sow the seeds for a life-long passion. In an antique shop on the Indonesian island of Sumba, near Bali, he found a piece depicting a woman giving birth. “I just bought it not really knowing what it was about,” Sebastian smiles. “At that age, you’re moved by things without realising their true significance – that realisation comes later on in life. It had a really strong impact on me. I was already collecting textiles and becoming fascinated by the way nature grew here.”

In his early 20s – during the mid-1990s – Sebastian went on to study painting at Central Saint Martins in London and Parsons in Paris. Put off by the chemicals his oil paints were laden with, he decided to travel to India in pursuit of creating his own natural pigments for his art. There, he began to work with Darshan Mekani Shah from Weavers Studio. She sent him to the village of Santiniketan, in rural West Bengal, where the philosopher Radindranath Tagore had founded an arts centre and school that combined Indian traditions with a humanist vision. This, in turn, prompted Sebastian to seek out a Santhal tribe by whom Tagore was inspired. In the village of Boner Pukur Danga, meaning the ‘land between the forest and the pond’, mud served as the material for buildings and furniture, down to the beds. On its outskirts, Sebastian found an abandoned house. Having tracked down its owner, he struck a deal: if he fixed the garden, he could stay there rent-free, which he did for three years. His neighbours, Lipi Biswas, a ceramicist and Bidyut Kumar Roy, who specialises in mud architecture, translated to help him communicate with the village, and supplied him with the minimal electricity he needed for his house’s single lightbulb. “Living like that, for me, that’s luxury,” Sebastian says. “There, I learned a lot about how you can enjoy nature more by living in an extremely simple way.” It was during this time, while working with a Muslim community of 80 women who specialised in hand embroidering fabrics that would take up to a painstaking eight months to create, that he immersed himself in the process of natural textile dyeing.

“Sometimes we try to move away from the past, but something keeps bringing us back to our path.”

SEBASTIAN MESDAG

In 2003, following in the footsteps of his uncle, Sebastian moved to Bali. “I really wanted to find a place that looked like the way things did when I was fourteen,” he says, exuding a nostalgia for the Bali of old that first captured his heart. Jungle abundant; pathways free of motorbike fumes; wildlife overwhelmingly present. “My uncle always said, ‘Whatever you do, move far away from Ubud.’ Because we had seen what happened in Spain where we were brought up: it became really developed.” Sebastian spent two years looking for the kind of land he’d envisaged. “I didn't want to hear the road. I didn’t want to see any electricity poles,” he says. Around the same time that he found the land in Payangan, his path intersected with Ayu’s; first fleetingly, then permanently. “I met him in Ubud near the football field,” Ayu recounts with a smile. “There was a festival we were waiting for. Two years later, Sebastian came back to Ubud. I remembered his face, but not his name. I met him again at the café, where I was waiting for friends to have a coffee. A few months after that, we started dating.”

Their second encounter took place in 2009; they’ve been inseparable since. Sebastian was required to convert to Hinduism to marry into Ayu’s family, a ceremony that involved the whole village. “I am a strong believer in all religions, but in their animistic side,” he says. “Hinduism in Bali is very different to Hinduism in India. For me, worship of Mother Nature comes first. When you are grounded, only then can you communicate with the higher god that is out there somewhere.” In 2010, the couple opened up a small jewellery store in central Ubud; Ayu forging her own creative path out of her family’s profession with her intricately gold necklaces, delicate earrings and rings. Meanwhile, Sebastian’s love of natural dyeing was calling him back. Alongside Ayu’s jewellery collections, they began to sell naturally dyed T-shirts and invested the profits into planting trees to reforest the patch of land on which they would eventually plant the indigo. “Sometimes we try to move away from the past, but something keeps bringing us back to our path,” Sebastian says.

Back then, the path that led through thickly forested jungle to their plot was a mud road; the land itself was brittle clay, punctuated by a few shrubs. Though the agricultural area traditionally received a lot of rain, village legend held that when villagers had rejected a visiting priest’s offer of water, his curse dried their water source up. A drought ensued for several years. No trees meant no shelter, causing strong winds to sweep away the family’s first bamboo structure, made of four poles and a plastic tarp. “We wanted to create a space that enhanced the land itself,” says Sebastian. “We really wanted to work with the elements, not against them.” For the first two years, they didn’t build. Instead, they constructed and slept in the small ‘Gladak’ where Ibu Kandri now lives while they got to know the land, taking time to determine the site and orientation of the house, and the position that felt right to sleep within it. According to Balinese spiritual tradition, the head, which represents the celestial and the heavenly, should point towards the north and the sacred Gunung Agung volcano, the island’s highest point.

Having determined their desired house position, Ayu and Sebastian began the Balinese ceremonial building process. As they were keen to build together with the village, as is local tradition, they enlisted one member of each of its fifteen families to help them. At that point, there was no electricity on site. Ironwood and teak salvaged from old Javanese buildings, some of them just shy of a century old, were brought up the dirt road onto the site and erected by hand. “Once we had the skeleton of the building, we brought it here. We started to put it up, then everything happened organically,” says Sebastian. “We had the wood, the workers, and then we created it together.” They built according to the characteristics of the materials, adapting the design to accommodate the length of substantial pieces of wood. The process took six years. “We weren’t working to a deadline,” he says with a laugh.

A pyramid-like roof references the typology of a traditional Javanese ‘Joglo’ house, revered for its craftsmanship and connection to nature, with an open interior structure crowned by a steeply pitched roof. “We wanted it to feel like camping,” Sebastian explains. “At the beginning, the building didn’t have any walls. Slowly we started to frame them around the landscape.” Separated from the village by a long road that dips down past horse stables – River loves to ride, like her father – the house can remain open. “It’s never been locked,” says Sebastian. “I like living like that, where I have no fear.”

A few years later, the family decided to add another structure to the property, dedicated to various facets of indigo production. A double-height adaptation of a Central Javanese ‘Limasan’ wooden house with a raised floor and pyramid roof, it hosts an indigo studio on the lower floor and the multi-purpose space for sleeping, sorting and meditating in which we awoke above. Inspired by Japanese minimalist philosophy, Ayu designed the structure to “blend the Javanese and the Japanese,” as she puts it, simplifying the skeleton and adding expansive windows to frame the mountain and jungle below. The studio took just over a year to build, led by a 27-year-old local builder and his father-in-law, who lived together on site during construction.

“Here, you can create this fantasy of a magical forest in your lifetime.”

SEBASTIAN MESDAG

As the studio was going up, so were the trees that Sebastian had planted. As a self-professed “plant freak”, he had set about realising his dream to rewild the previously barren land while creating a self-sustaining ecosystem for the indigo plants that chance had planted in his life. Sebastian asked each builder from his village to bring a seedling of a tree from their land. He quickly came to recognise the saplings of local trees, and continually collected cuttings and planted seeds. Slowly, a modest nursery began to take shape across the land. Alongside abundant lush-fronded tree ferns, there are bodhi, banyan and ficus trees. A quintessentially Australian ghost gum stretches skywards. Fifteen years since its planting, one ficus tree now needs three people joining hands to reach around its trunk. The priest’s curse appears to have lifted. Rain falls freely. “Things are starting to come back. The valley has a spring that’s now full of birds. The other day, we heard a bird we’d never heard before. There are fireflies at night,” Sebastian says. The pace at which everything grows in Bali delights him. “Here, you can create this fantasy of a magical forest in your lifetime.”

Now, the forest has its own magic to make – a natural microclimate for the family’s indigo plantation that began from those three plants that Sebastian cut and replanted until he had enough leaves to make an indigo paste; 500 grams requires four kilos of leaves.

After three to four months of growth, the plants are ready to be harvested, which happens in the morning, following a traditional practice. “We cut the plant to about 20 centimetres from the ground,” Sebastian explains. “Then we pluck the leaves and soak them for two days until the dye starts to come out.”

Tian Taru’s recipe originates from the couple’s friend, the ceramicist Edith Strickler, and is adjusted for less lime, which Sebastian is experimenting with removing altogether. Once the leaves are taken out of the vat, limestone is added. The vat is then aired so that the indigo particles attach to the lime and settle at the bottom overnight. The next day, the water is separated from the indigo particles, which are collected through a sieve and worked into a paste. The paste is then added back into the vat together with palm sugar cultivated from the neighbouring village, a bit of lime and hot water. “We wait another day until it’s active,” says Sebastian. “Then we can start the dyeing process.”

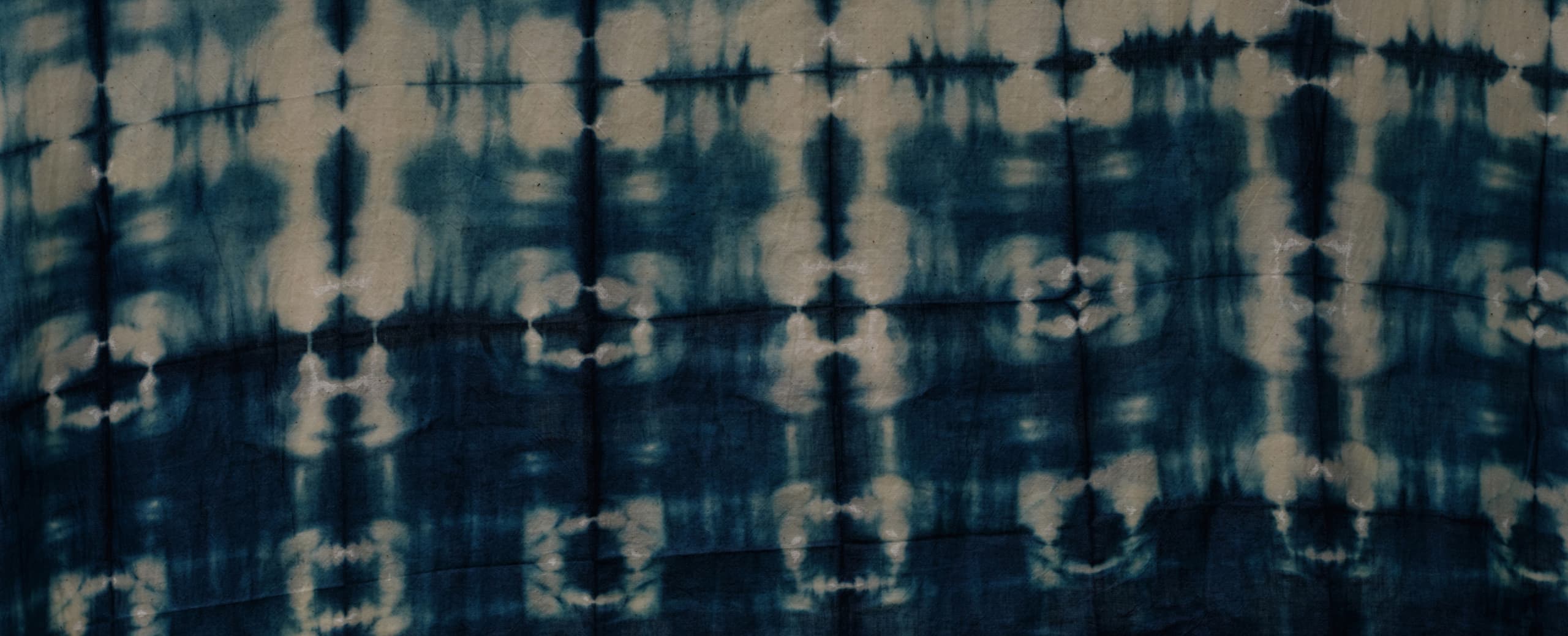

On the grass in front of the house, Pak Andika and his colleague have the vats ready. As they expose the liquid to the air, the colour transformation becomes visible. It tints from turquoise cut with a glinting yellow to an inky midnight blue, which stains their hands as they work oxygen through the elixir. Swathes of liquid pour through the air and back into the foaming vat, turning into an ever-darker midnight blue. It’s mesmerising to watch, as is each stage of the dyeing process, which Sebastian describes as an exercise in slowing down.

“You can’t rush any part of it,” he says gently. “You have to be attentive.” It’s this element that challenges and captivates guests to Tian Taru’s workshops. Held around once a month, on an ad hoc basis to accommodate the schedule of Tian Taru’s team of nine, as well as frequent local ceremonies, the day-long sessions each take two to three days to prepare. “We try to put as much detail as possible in everything that we do,” says Sebastian. “But with simplicity; not too much,” qualifies Ayu.

“People say, ‘This is so relaxing!’ It takes them back to their childhood. They’re like little kids again, laughing.”

AYU PURPA

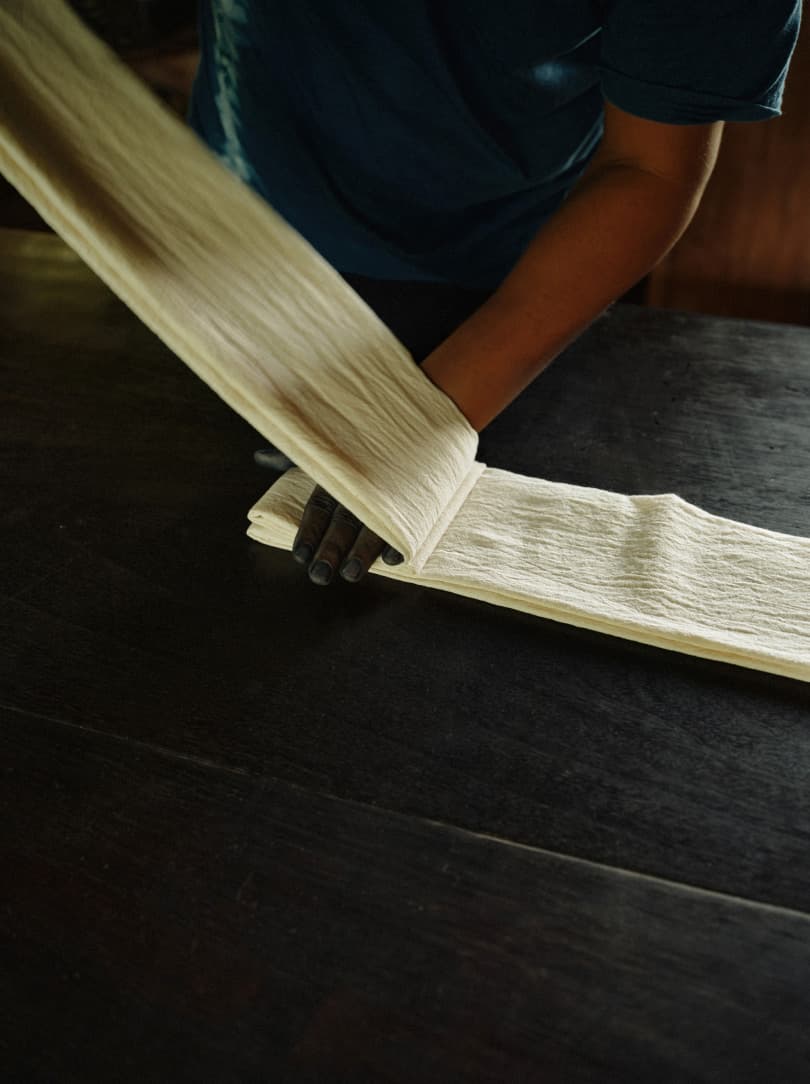

As participants of the workshop, we have been asked to bring an old piece of clothing to breathe new life into, and receive a shawl of raw handwoven cotton to dye.

We will leave not only with two new textiles, and hands stained in inky blue, but with our own indigo cutting and extensive knowledge about the indigo growing and dyeing ecosystem. Several of the guests in the small group – capped at nine to enable everyone to get dedicated support and attention – are in fashion or other creative industries, and are interested in learning skills to adapt in their own practices. A few have come up from Bali’s south-western coast around the heaving tourist towns of Canggu or Seminyak. “Most people get stuck down there. They haven’t seen the real Bali,” notes Sebastian. “When they come up here, they’re in awe.”

After being welcomed onto the land, we are taken through a condensed version of the entire indigo ecosystem, from plant to finished fabric. We begin with a walk through the indigo plantation at the property’s edge, where Ibu Putu, Ibu Komang and Ibu Kandri demonstrate how they harvest the plant using traditional sickles. They gently place bushy bundles of leaves into woven baskets carried on their backs. “We explain the kind of place you have to create to be able to plant Assam, as well as its characteristics,” says Sebastian. After the harvest, we move back into the space above the indigo studio to pluck the leaves. Seated together on the floor with traditional cutting tools in our hands, the excitement is tangible. Ayu will later tell us, “Many people say, ‘This is so relaxing!’ It takes them back to their childhood. They’re like little kids again, laughing.” She’s right: here, between pillars of centuries-old wood that frame the natural jungle tapestry, time seems to stand still. The inessential has relinquished itself.

“It’s like magic; you see the blue appear in front of your eyes.”

SEBASTIAN MESDAG

Leaves plucked and spirits revived, we head downstairs to the dyeing studio, where the pre-prepared vats have been lowered into purpose-built cavities in the clay floor. We’re each encouraged to select a pattern or design for our fabric. We select from a variety of simple pattern-creating tools – solid round clamps or rubber bands – to protect the areas where we want the textile to keep its original colour. Then we approach the vat, crouching down to dip the raw fabric deep into the midnight-blue abyss. “When you take the textile out of the vat, it’s a yellow-green. When it has contact with the air, it starts to oxidize and turn blue,” explains Sebastian. “It’s like magic; you see the blue appear in front of your eyes.” When people see the results, they clap, Ayu notes. The more times a fabric is dipped – with pauses in between – the darker it becomes.

As our final pieces dry on a clothing line strung up in front of the tree ferns that fringe the lawn and we break for lunch, a sense of pride is palpable. For a single pigment, indigo’s range and depth are remarkable, reminding us that it is a living colour. In this moment, indigo’s mystical alchemy reveals itself to us; the simple act of dyeing transcending the colouration of fabric. As Sebastian remarks, “The fibres carry something more special.”

It’s not only cloth that acquires a rich indigo hue at Tian Taru. In addition to the workshops they host, Ayu and Sebastian often collaborate with artists, which offers them new opportunities to test their dyeing methods on different materials. Often artists will stay for a longer period of time in a residency of sorts, sleeping in the space above the studio and eating together with the family, like we were invited to do. Collaborations have seen them colour Himalayan goat hair with Uluwatu-based American artist Spencer Hansen, a chair with Indonesian contemporary furniture designer Eva Natasa, and banana paper with Naruse Kiyoshi of Greenman Banana Paper Studio. Ayu and Sebastian created a three-metre-long vat to dye teak for an entire indigo room as part of a new house, Kubu Taru, which is taking shape in collaboration with local architect Conchita Blanco and Avalon Carpenter from the woodworking studio Kalpataru.

Sharing with and learning from other keepers of indigo around the world is central to Tian Taru’s purpose. Letting a recipe slip once meant losing a competitive advantage, and accordingly a livelihood – if not a life. Sebastian has heard that Japanese indigo masters could be sacrificed for revealing secrets. Today, however, sharing centuries of lost knowledge is essential. Recently, Tian Taru welcomed the indigo artists Thinley Delma and Karma Lhazom from Bhutan. With plans to open their own indigo studio in their home country, the duo wanted to learn how to grow a plantation themselves, as the harvesting of wild-growing indigo from the forest is forbidden there. In turn, Sebastian reciprocated the visit, eager to learn the traditional – and in his view, more sustainable – Bhutanese vat recipe, which foregoes limestone and sugar altogether. Instead, the leaf is left to dry, then wet to make a ball and buried under cow dung, whose heat catalyses the fermentation process. After two to three weeks, it is added to the vat together with lye water and rice wine. Soon after, the bacteria activate to create the indigo colour.

Sebastian is keen to try to adapt the process at Tian Taru to create a vat that only uses materials on the property. Yet the volatility of the bacteria and the cooler climate in Payangan need more work to perfect. The experimentation continues. Rather than expanding into production or quickening the pace of their workshop schedule, Ayu and Sebastian are intent on venturing deeper into the nuances of their craft. They’re exploring aligning cultivation and harvest to moon cycles, in keeping with Balinese tradition. Plans to open a gallery dedicated to the entire indigo ecosystem are in the works. Yet just like the plant to which it is dedicated, Tian Taru remains veiled in elusiveness. Like all things rare and precious, it evades convenience, immune to the pace of the modern world and unfazed by its shifting demands.

As the day dips into evening, the trees continue to climb towards the sky, branching out their fronds and leaves to shade the mysteries of the plants growing below. While we fold away our new creations and prepare to set back out into the world, dusk washes the distant mountain and its jungle in the deepest blue.